Film and Feminist Chats: Beyond Sorry

Join us for popcorn, good chats and movies, at Library at The Dock, on 7th of ...

Content warning: discussion of suicide and suicide ideation; dismissal of AFAB experiences of mental health; mention of drug use; stigma and discrimination

“I’ve been calling Lifeline since I was 13”

I’m now 48 and what’s called ‘suicidal ideation’ has been a fairly constant companion of mine for 35 years.

When we think about mental health issues, we often think of it in terms of crises, of people having psychotic episodes and imagining they can fly, or falling into deep depressions and attempting suicide. Our entire mental health system with its subsidised 10 sessions with a psychologist is predicated on this idea, that mental illness is a short-term thing, solved with some counselling, crisis intervention and maybe some pills.

And for some people, that’s true.

For many of us though, mental illness is chronic, and sometimes it’s structural and societal rather than individual and internal. Over many, many years of being in the mental health system, I’ve developed a layered, nuanced understanding of which bits of my mental health are genetic, which bits familial, which bits cultural and which bits just a mystery.

Like many women and nonbinary folk who are assigned female at birth, I’ve seen mental health categorised as ‘hysterical women’s problems’. I remember as a teenager reading all of those harrowing autobiographical stories of women’s experience of mental health — Frances Farmer and Sylvia Plath and Charlotte Perkins Gilman — and wondering whether my fate was to be incarcerated or to die and which would be preferable.

In my early teens, the diagnosis was oppositional defiant disorder. In my late teens, I was out of control, taking drugs to cope with life. In my 20s, the diagnosis was bipolar disorder. In my 30s, there were questions of borderline personality disorder.

During all this time, I called Lifeline. As a teen, because I really felt like I wanted to die and it scared me. In my late teens, because friends had suicided and because I felt like my behaviour was becoming reckless and it scared me. In my early 20s, I’d call after a binge. As an adult, I’d call when work stress was overwhelming and I felt like my life was spiralling out of control. Sometimes, I would call just to talk. Sometimes I would call to say, I’m scared I’m going to do something I’ll regret, will you talk with me while I walk from the city to Clifton Hill?

At 43, after my child was diagnosed as autistic, I went back for a fifth opinion and a Professor of Psychiatry gave me the latest label: adult ADHD with autistic traits. The ASD clinic in Kew said that they were certain that I would have been diagnosed as autistic as a child — if we’d known back then that women and people who could speak as well as me could also be autistic — but that as an adult I’d used my high intelligence to accommodate for myself too much, and now I didn’t fit the criteria for a disorder any more. They called it ‘autistic spectrum condition’ instead. And they said the main challenge for me would be dealing with the trauma of trying to fit into society for so long with no help.

It was the first time in my life that I’d heard the idea that my mental distress — my trauma — might be because society didn’t accommodate people like me rather than that there was something fundamentally wrong with me. This idea — known as the social model of disability as opposed to the medical model of disability — was transformative for me.

It didn’t stop the suicidal ideation — that constant companion of wondering what it would be like if I went through with the distressing thought in my head — but it made more sense of it.

The psychiatrist gave me Reboxetine for the ADHD and I started reading about executive dysfunction. I started to understand that taking amphetamines in my late teens was a form of self-medication.

I started posting about my mental health on social media. One of my friends, who had a pharmacology degree and a fascination with genetics, started suggesting I look into a collection of gene polymorphisms — related to how we process B vitamins — that fit the symptoms I was describing. We’ve known for a while that the gut and mental health are connected, and I already knew that I and my siblings were coeliac and that autism has a genetic component, so the idea that there could be another genetic component to my story didn’t surprise me. B vitamins are vital to handling stress, and to creating happiness, and to building the chemicals in your brain that help you pay attention.

Surprise, my friend was right: both copies of the gene to turn vitamin B9 into a form my brain could use were broken. I started to take an activated form of the vitamin, called MTHF, and slowly tapered off Reboxetine. I was calmer and more able to withstand stress than ever before in my life.

I didn’t stop going to therapy, of course — 10 sessions a year, trying to juggle extras when the rebate ran out. And I didn’t stop calling Lifeline either — I just called them earlier and earlier in the process. I called to say, hey, I can feel that dip coming, I don’t want to waste your time but I’m also leaning on my friends too much and they’re sick of hearing about it. I started to notice a pattern: I was calling every two months. I started hearing from friends about PMDD, a form of pre-menstrual tension that caused extreme dysphoria and suicidality in some of us. Could it be possible, with only one ovary showing signs of polycystic ovarian syndrome, that I would get PMDD every other month? My doctor was dismissive, but I’m still suspicious.

Even though I’ve uncovered so many underlying causes for my poor chronic mental health, it doesn’t take away from the experience of it. It still means that my resilience is fragile and when work stresses combine with personal stresses and coincide with the wrong month in my cycle, I can still get severely distressed. The most recent instance was only three months ago and I imagine I’ll be having these episodes for the rest of my life.

I don’t think my story is particularly more complex than others with chronic mental health issues. I just don’t think we talk about it very much, and that for far too long, medicine has focused on the experiences of cis- men which means not much is known about the health and bodies of women, intersex, nonbinary and trans folks. That, combined with the stigma of acknowledging chronic mental health issues — I’m using a pseudonym for this story because I’m worried a future employer would use it against me rather than seeing the bright, creative, competent person I also am.

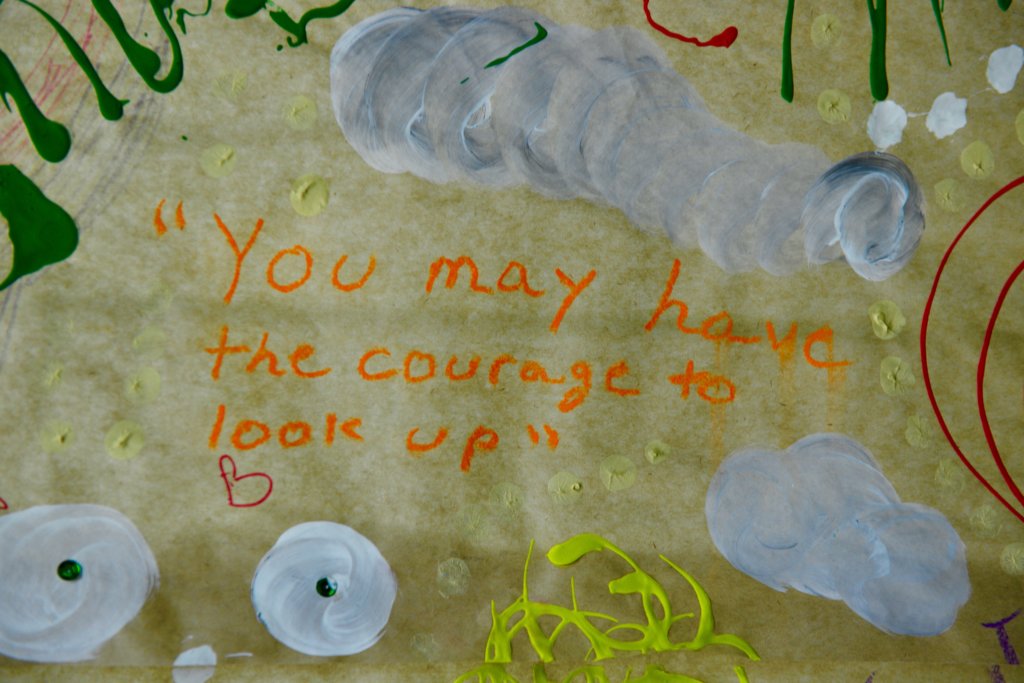

So what helps, now, is just knowing that I’ve been here before, and that I’m resilient as all get out, that I can do this.

I advocate for myself and demand accommodations, in workplaces, at events, during social occasions. I use quiet spaces at conferences when neurotypical noise levels and fluoro lights are overwhelming, knowing these are external structures not internal failings.

I can call Lifeline, yet again, and laugh with them about having called them for 35 years solid, and still being here to call them again.

I can drag myself out of bed to have a shower, even if it’s the only thing I do that day.

I can make a plan to do something I love in two or three days. It doesn’t have to be massive, just something that I’m looking forward to enough that not being here for it would be really disappointing. I take walks with the dog in green spaces, by rivers.

I can text a friend and say, not doing so well, even if I don’t feel like I can ask for help yet, and know that they will probably turn up at my house with home-baked gluten-free gingerbread because they know it’s my favourite.

I can remind myself that a good deal of why I feel like this is because of my genetics, and my history and a patriarchal system that chronically underdiagnoses women and nonbinary folks and left me to fend for myself for far too long.

Oh — and finally, what supports me is a community of fabulous autistic feminists who share our stories and see each other, strong, courageous people, holding it together, one day at a time.

If this article brought up issues for you or thoughts of suicide, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. If life is not in immediate danger, but you’d still like to chat, call WIRE on 1300 134 130.